When the Vikings arrived in Ireland, there were no towns but 400 monasteries. Imagine that. I stumbled upon that piece of information recently, and it reminded me of a documentary I saw on Irish television some years ago. It was about an Irish couple who had an interest in Tibetan Buddhism. They had been visiting Tibet and the monasteries there, and at that time they struck up a friendship with one of the monks. In time, they invited him to come to Ireland. They were excited to show him some of their own spiritual heritage, some of the rich history of early Christianity, and the sites of former worship by the early saints. Their Tibetan friend came, and off they went on their trip. Yet with each passing day, a heavy sadness descended upon the Tibetan monk, until eventually they had to ask what the matter was. I’m sad, he told them, because Ireland 2000 years ago was just like Tibet today, but you have lost it all, and it makes me sad for what is happening in my home now. I lose hope.

Ireland was once like Tibet. Imagine that.

Ireland is quite unique in one sense, for often when one tradition encounters another, the stronger one will try to eradicate the weaker. But not quite so in Ireland. When Christianity first arrived and encountered Paganism, a process of “syncretism" began.

Syncretism refers to the merging or blending of different beliefs, practices, or traditions into a new and harmonious synthesis, often describing the process where elements from multiple cultural or spiritual traditions are combined, resulting in a cohesive and integrated whole.

This, of course, is a very complex and nuanced aspect of Irish history and spirituality. For now, I just highlight the idea because it is a topic I intend to touch on throughout these posts. There is a rich tradition of early Christianity in Ireland—a Celtic Christianity, if you wish—that I believe can teach us a lot about how to lead a good life. In particular, it can teach us to live more in harmony with nature, for this is a central pillar of its message: the natural world is a gift of God and a pathway to God; his creation is all around us. In my own way, my posts about nature and nature connection are calling to this aspect of spirituality and of encountering the sacred.

But today, as we approach St. Patrick’s Day, my mind is turning to the lives of some of those early saints—the green desert fathers, as some call them. And in particular to St. Kevin.

St. Kevin was born in the late 5th century, possibly around 498 AD, in the region of Leinster. According to legend, he was born into a noble family, but he chose a life of religious devotion and solitude. When you read a little of his story, you can just imagine how he only wanted to live in his tiny hut, away from distractions and people, in order to live a life of prayer, silence, and contemplation. But God had other plans. St. Kevin drew attention to himself, and soon enough, a monastic village built up around him on the shores of Glendalough, along with the responsibilities of leading his followers.

Glendalough became a sanctuary for me. When I lived and worked in Dublin City in the early 2000's, it was the nearest place, and just far enough away, to help me feel I had escaped from the city and into nature. I would take the only bus to Glendalough, St. Kevin’s coaches, that left at 9 a.m. each morning, arriving at Glendalough at 11 a.m. and giving me five hours to disappear off into the forests or up the Spink to traverse the heights above the lakes. I loved it there, and I still do. And always, the presence of St. Kevin was about the place—the vague outline of St. Kevin’s bed seen from the far shore, the round tower reaching up above all else, the altar of the main church exposed to the elements with the wooden roof long since gone, and the small monastic cells with their low arched entrances. All of this is nestled in the pleasant nature of Wicklow, with the willow, ash, and oak trees and the brown, coppery waters of Abhainn Ghleann Dá Loch rushing by.

Invigorated by the walk and with some time to spare before the bus returned to Dublin, I’d often pop into the bar of the Glendalough Hotel for a pint of Guinness. Is there a better way to spend a day? Though I didn’t know it at the time, in my own stumbling way, I was embarking on a small pilgrimage each time I went. I intend to return again this year.

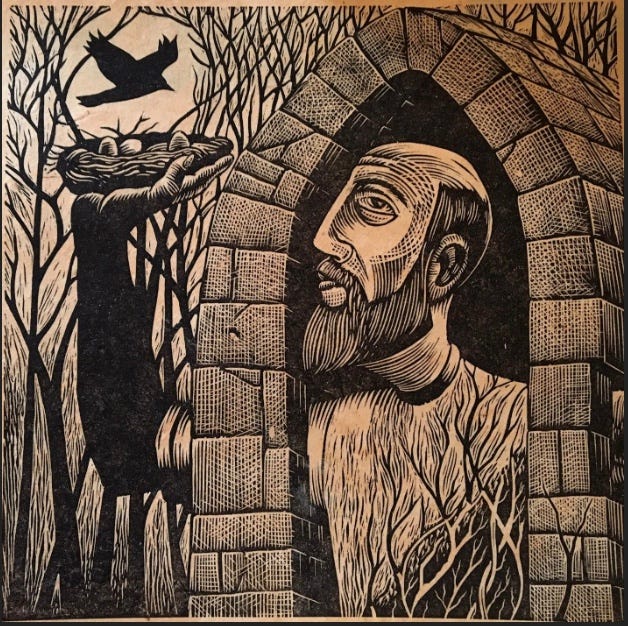

What many remember of St. Kevin is his communion with the natural world. One of the most famous legends associated with St. Kevin is the story of the blackbird. According to legend, while St. Kevin was praying with his arms outstretched in solitude, a blackbird nested in his hand. Despite the discomfort and distraction, St. Kevin remained motionless so as not to disturb the bird until it eventually flew away. Besides birds, it is said that other wild animals would approach him, including foxes, deer, and wolves.

Wouldn’t it be nice if there was a National St. Kevin’s Day when everyone was encouraged to take the day off and go for a long walk and sit in nature somewhere? There’s a simple practise to help us tune into the Spiritual heritage of Ireland, to help foster connection with the world around us, to help alleviate the disconnection and lack of meaning so many of us feel. A canopy of trees above us is no different than the vaulted roof of a cathedral. St Kevin knew this well enough.

St Kevin and the Blackbird

And then there was St. Kevin and the blackbird.

The saint is kneeling, arms stretched out, inside

His cell, but the cell is narrow, so

One turned-up palm is out the window, stiff

As a crossbeam, when a blackbird lands

And lays in it and settles down to nest.

Kevin feels the warm eggs, the small breast, the tucked

Neat head and claws and, finding himself linked

Into the network of eternal life,

Is moved to pity: now he must hold his hand

Like a branch out in the sun and rain for weeks

Until the young are hatched and fledged and flown.

And since the whole thing's imagined anyhow,

Imagine being Kevin. Which is he?

Self-forgetful or in agony all the time

From the neck on out down through his hurting forearms?

Are his fingers sleeping? Does he still feel his knees?

Or has the shut-eyed blank of underearth

Crept up through him? Is there distance in his head?

Alone and mirrored clear in Love's deep river,

'To labour and not to seek reward,' he prays,

A prayer his body makes entirely

For he has forgotten self, forgotten bird

And on the riverbank forgotten the river's name.

Seamus Heaney