First Impressions

Before we begin, rest assured—though we’ll be speaking about holly in this post, there will be no mention of a certain time of year beginning with ‘C’, when holly has a special use. Nobody in their right mind is thinking of that particular season in late June, nor do they want to read about it. Now, let us proceed.

I’ve been sitting with the holly tree these last few days, every so often letting its presence occupy the quiet recesses of my thoughts, while steering clear, for a time, of its ecological, medicinal, or practical aspects. What, I asked myself, do I think of when I think of the holly?

What came to mind first was a song I once heard around a fire some years ago. A song that stayed with me. It was sung by a young man taking that courageous step of sharing a song for the first time—a young, idealistic fella flexing his muscles through early manhood, learning about land and nature connection, looking for that nature cure after an upbringing in the notoriously rough housing estates of Tallaght.

He sang:

And the first tree of the green woods it was the holly.

Holly, ho-o-lly, Oh the first tree of the greenwoods it was the holly.

He sang it well—unpretentiously, earnestly—and as I listened, I found myself asking: Why the holly? Why would holly be the first tree of the green woods? So significantly so that they would write a song about it.

I never looked for an answer to that question. I could do so now, but I won’t. That would require following some internet pathways. On this occasion, I prefer to revert to the old ways, that is, I’ll wait until I hear the song again, if ever it happens, and then I’ll raise the question: Why the holly? Somebody may know. But if not—well, the journey continues. I may never find out. There may be no answer. But the song stayed with me, as songs did in times gone by, when they were heard among gathered company. A song, like a treasure inside a bag, carried by someone wherever they roamed and revealed to those lucky enough to hear. A question unanswered can be as valuable as one answered at times, it holds a force, pushing us forward.

When I picture the holly, I also see in my mind’s eye the oak forests of Killarney—and to explain why, we must slip into some notes on ecology. Holly is an understorey species. It grows beneath the canopy of ‘climax’ trees like the oak and the ash—but especially the oak. In a healthy, natural woodland you’ll find holly growing amidst the oaks, thriving under their thick canopy, in the shade they cast. Often intertwining with them, even taking root alongside them, coiling like a snake around their trunks.

In my mind’s eye I see the dark, glossy holly leaves in sharp focus before the fissured, mottled brown of the oak trunks. Throughout the year, in all seasons, the holly holds those leaves and brings a bright wash of deep green at eye level throughout the woodland. And out of that dark green cover, a wren or a robin might flash past you as it alights from its shelter. They are thankful for the holly—for the opportunity and the protection it provides.

And I think of cows in the field, circling a lone holly tree. Take a closer look, once the cows have parted, and you’ll see evolution before your eyes. The holly has evolved to protect its lower leaves from browsing animals by making them sharply pointed—that classic holly leaf we know so well. But further up, beyond the reach of teeth, the leaves lose that sharp edge and smoothen out, safe from threat. But stumble upon a holly growing in a place that grazing animals have never passed and you might find one with little or no spiky leaves, thus showing that this adaptation is still responsive to the local environment and not just some ancient conditioning.

Ecology

From an ecological perspective, holly is not merely a decorative feature of the woodland understory, it is a lifeline through the leaner months.

As one of our few native evergreen broadleaf trees, holly provides year-round cover and structure in the forest. In winter, when much of the deciduous canopy is bare, holly holds its dark green leaves, offering critical shelter for birds who flit through its dense boughs seeking refuge from wind and cold.

Its berries, too, are a lifeline. Though toxic to humans in large amounts, the bright red holly berries are a vital food source for birds, particularly the mistle thrush, who is known to fiercely guard a fruitful holly tree in winter as its own private larder. The berries ripen in late autumn and persist into the depths of winter, precisely when food is most scarce.

Holly is also a dioecious species, meaning male and female flowers grow on separate trees. Only the females bear berries, and only if a male tree is nearby. This often-overlooked fact speaks to the subtle interdependency within the woodland, pollinators such as bees and hoverflies are needed to carry pollen from one tree to another.

And though holly can grow in open ground, it thrives best in the understory of mature deciduous woodlands, especially as mentioned under oak. There, it contributes to woodland succession, shade tolerance dynamics, and vertical diversity. The thick holly canopy also helps suppress excessive ground-level growth, making space for ferns, mosses, and fungi to flourish.

In time, holly becomes a kind of elder of the forest, it may never reach the towering heights of the oaks but it holds no less an important presence in the woodland.

Folklore

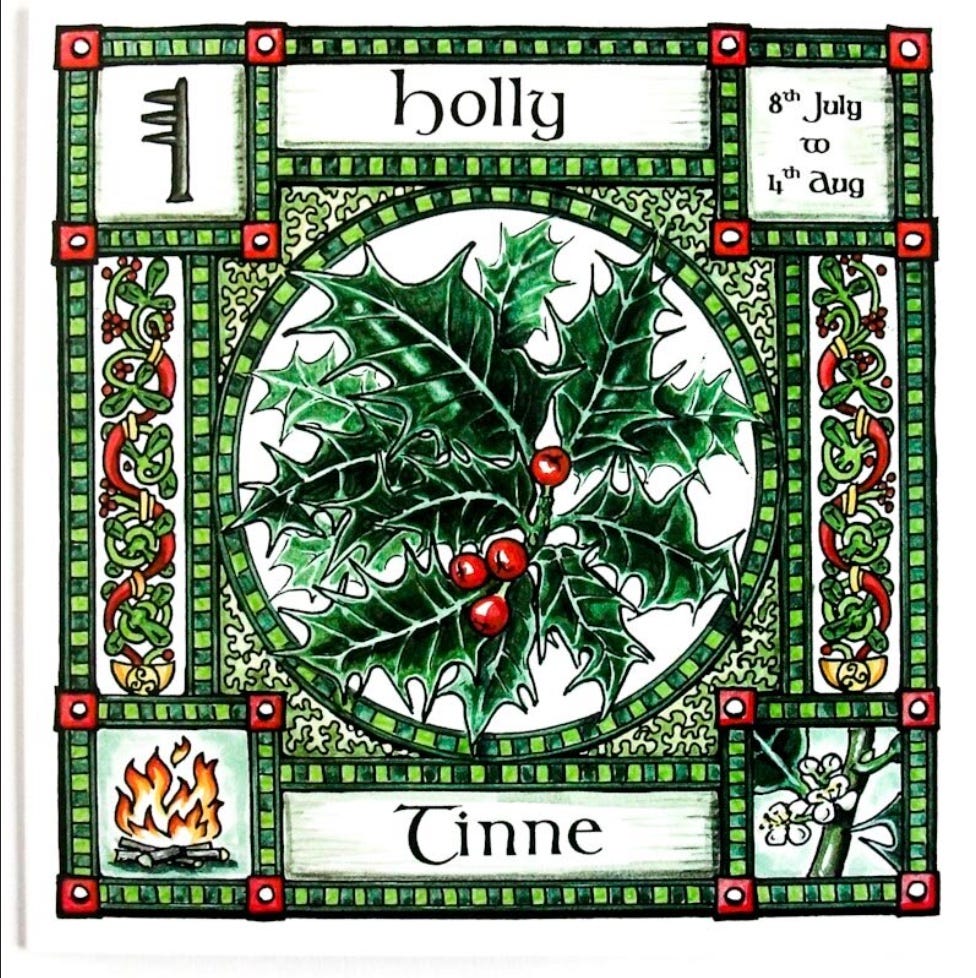

In the Ogham calendar, holly is associated with the letter Tinne and corresponds to the period around July 8th to August 4th, marking the height of summer’s strength just after the solstice. As a symbol, Tinne (meaning "bar" or "ingot of metal") reflects the holly’s connection to protection and endurance. In this midsummer phase, holly teaches us about holding our centre through challenges, and embodying resilience before the gradual return of the darker half of the year.

So the holly is native to Ireland, intertwined with our soil, our seasons, and our heritage—a key species in our woodlands. But its significance reaches further still.

To walk with the holly is to brush up against something deeper, not just ecology. For in our folklore, the holly is more than a tree. It is a guardian, a symbol of resilience and endurance through the darker half of the year. It stands evergreen when all else fades. It remains as seasons turn.

In Irish tradition, holly was long considered a sacred tree. It was often planted near homes as a charm against lightning or ill-wishing. The spiny leaves were believed to ward off malevolent forces, both natural and unseen. In some areas, people would never cut down a holly tree entirely, believing it brought misfortune to do so. Even today, many older people will think twice before interfering with one.

In the old myths, holly can be seen as the tree of the warrior spirit. It was said to be the wood of choice for spear shafts, its wood grain is tough, holding something of the essence of battle and endurance. Some scholars trace the tree back to the Holly King, one of two symbolic rulers of the year in Celtic lore, who governs the dark half from the summer solstice to the winter. His opposite, the Oak King, rules the light.

So the holly stands not only in the shadows of oaks, but in mythic opposition to them.

Holly Medicine

Medicinally, while the holly is more commonly revered for its symbolism than its curative power, there are threads of folk medicine woven through its story. The leaves were sometimes dried and steeped into teas as a remedy for fevers or to support the body’s natural cleansing, used sparingly and with respect, for the plant holds a potency not to be taken lightly. The bark, too, found occasional use in traditional preparations, though such practices were rare and deeply localised. Its berries, bright and alluring, are in fact toxic to humans in any quantity, a reminder that not all medicines come in gentle form.

Farewells

The day before writing this piece, I walked in a woodland with friends, and since the holly was on my mind, it came into greater focus. The woodland had not evolved in a fully natural state—the hand of man was evident here and there: non-native species, clear-felled plantations, and replanting of Sitka spruce. Natural woodland straddled commercial forestry, taking us through groves blessed by oak or ash into areas strangled by invasive laurel, which leaned across the pathway like a vaulted roof, blocking out the light. Amidst it all, the holly stood small, ancient-looking even, at times like a 4-foot bonsai, growing and making its presence known. Each one I saw was a reminder of nature’s desire to return to balance. The holly was native, at home, slowly returning to the woodland and paving the way for that balance to be restored. Each stand of bright grey bark and dark, threatening leaves was actually a wish for harmony—a prayer for the natural order, a call to return this place to a thriving native woodland.

That task, of closing my eyes and checking in with what the holly evokes in me, was a quietly nourishing experience. It was an acknowledgment that the holly, whether I’ve been aware of it or not, has been a companion on countless walks: a steady presence in the land I call home. Each of those encounters, whether fleeting or significant, pleasant or otherwise, has been like a drop in the pool of my impressions, shaping the ecology of my inner world. To bring that to light and observe it with attention felt like an act of respect—for the tree, and for my own being.

The Bach Flower Remedy Holly is used for people who are attacked by thoughts of jealousy,envy,revenge,and suspicion.

It brings about balance and ease.