One Word at a Time

Reclaiming the Living Landscape Through the Language of Attention

Today I want to make you an invitation — but first, let’s take a walk.

From the house with the gabled roof, perched on the hill above Myrtleville in South Cork, I look out toward the Hill of the Black Crows (Cnoic na bPréachán Dubh) — a stand of sycamore, evergreen spruce, and pine that is home to a large rookery. The birds caw and clatter through the sky, landing their black silhouettes on the pylon wires, venturing into the gardens, side-stepping with that watchful, deliberate turn of their dark-feathered necks. They are calling now, as I descend through the garden, passing beneath the spruce that has been wind-blasted bare on one side.

I come to the Little Cove of Golden Sand (An Cuanín Ghaineamh Óir). It’s early evening, and most people have gone home, but a few bathers still wade knee-deep through the water. A father looks out at his two young daughters. By the rocks, a couple gather their things, chatting softly about this and that.

I follow a thin, mucky path that threads behind the coastal rock faces — those old grey jaws cracked and groaning toward the sea. I pass the Place of the Yellow Flowers (Áit na Blátha Buí) at the foot of a steep, earthen cliff. The flowers are blooming now — a long-season bloom — their yellow faces open to the salty spray, thriving.

Stepping stones lead me into a curious stand of young bamboo, whispering in the breeze like the low murmur of foreign visitors. The path leads to a second beach, this one entirely made of smooth, rounded pebbles heaped into steep piles. I skid down one slope to the water’s edge and arrive at my destination — a great boulder known to me as

An Carraig a Bhaineann leis an bhFarraige — The Rock that Touches the Sea.

I sit beside its great black face and look out — toward the cargo ships waiting to enter Cork Harbour, toward a seagull or two rising and falling above the water, and toward the cream-white bodies of others perched quietly on the shore. The waves pull the pebbles over one another in a soft clatter, like the final sounds of the day.

Language as Landscape

That short walk — no more than twenty minutes — changed in texture and meaning as I named it. As I gave names to things, they became more than background; they came alive for me — present, vivid, as though brought into focus after being long blurred.

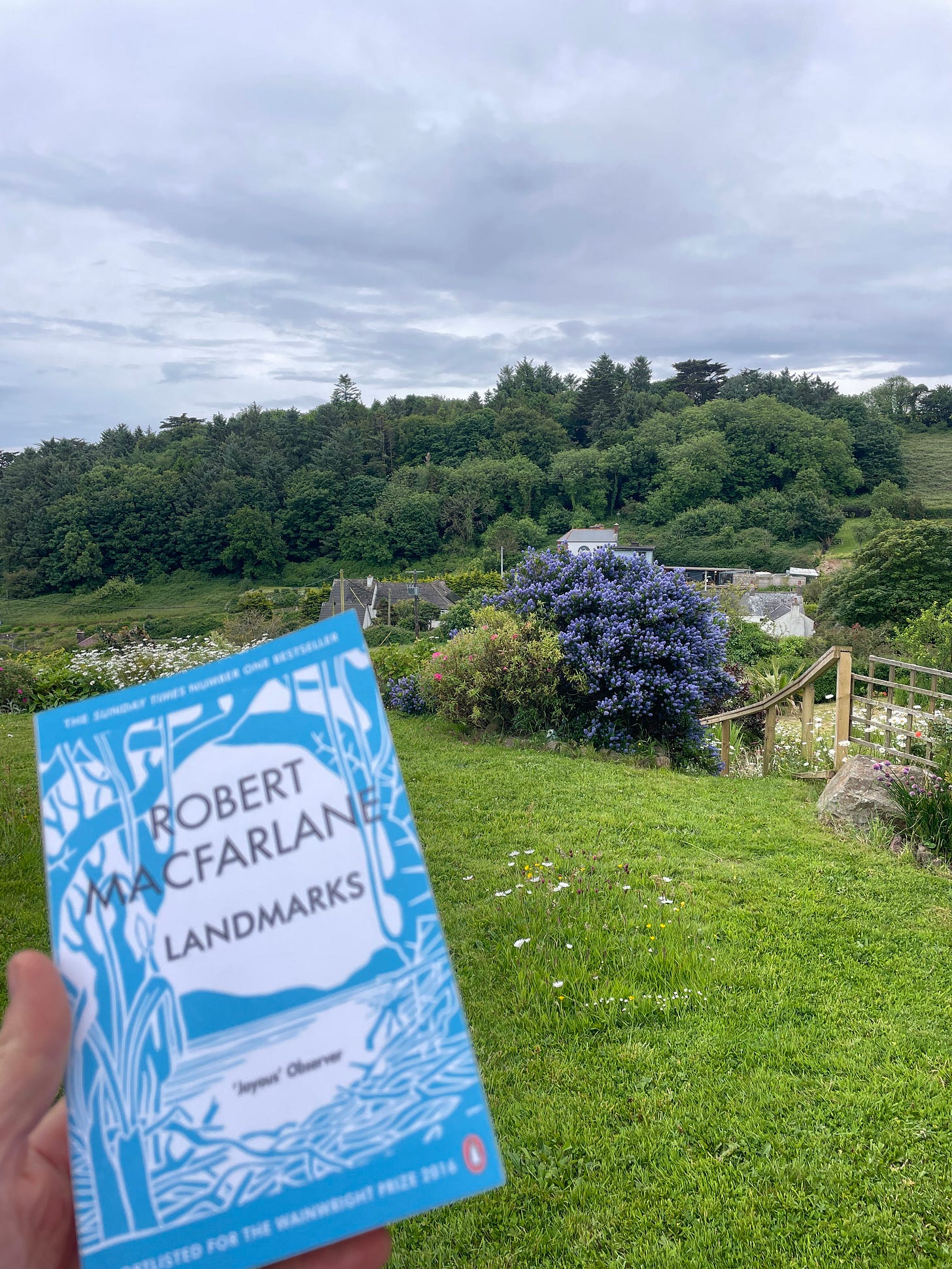

I’ve been pondering this more deeply since picking up a book this week: Landmarks by Robert Macfarlane. In it, Macfarlane explores the ancient and often vanishing words once used to describe the landscape — words that belong to particular places, seasons, textures, and ways of being in the land. He reminds us that language is not just a tool to describe the world, but a way of seeing it. To name a thing is to notice it. And to notice something is the beginning of caring for it.

In the loss of these words, Macfarlane warns, we are not just losing poetry — we are losing perception itself. The land flattens into what he calls a blandscape — a place stripped of texture, specificity, and spirit. Where once every hollow, stream, slope, stone, and flower might have held a name — and with it a story, a function, a relationship — now they pass unmarked and unnoticed. As if they are not there at all.

But we can remember.

We can reawaken our noticing.

As I read through the book — which includes glossaries of forgotten words, and vivid portraits of writers who have most deeply embodied this way of seeing — I found myself longing to experience it directly. I didn’t want to just think about these ideas; I wanted to live them. To take the words off the page and return them to the world.

So I put the book aside, gathered a pen and paper, filled my water bottle, laced up my shoes — and walked the same path I’ve walked countless times before. But this time, I brought my attention with me. I walked with the quiet task of naming what stood out, of giving language to what drew me in.

It was such a simple act.

And the result was profound.

Things that had become background, that I had passed a hundred times without thought, suddenly stood before me with presence and character. Naming them did not contain them — it revealed them. It gave birth in me a renewed relationship, indeed it allowed us to exist in relationship.

So here is my invitation to you.

Take a short walk today, or sometime this week. It doesn’t need to be wild or remote — even a city park will do. Bring with you a listening heart and a playful mind. As you walk, allow yourself to notice what calls to you — a twisted tree, a sunken patch of earth, a certain bend in the path. And then give it a name. A real one. A poetic one. A made-up one. A native-language one. It doesn’t matter. Just name it.

As I walked that path, I found myself imagining what it would be like to walk it with a group — a small community of people, each noticing, each naming. I wondered what we might call each place together. That is how it was of old. Naming was a communal act — a weaving of relationship between people and place. In this way, names became a living map. And the landscape, in turn, became alive.

In Landmarks, Robert Macfarlane writes about the disappearance of nature words — like “acorn,” “bluebell,” and “conker” — from the Oxford Junior Dictionary, replaced by the language of technology: “attachment,” “broadband,” “chatroom.” He warns that the natural world becomes far more easily disposable if it is not named. That when we stop naming things, we begin to stop seeing them.

But to name is to notice. And to notice is to love.

Macfarlane calls for what he beautifully names a “Counter-Desecration Phrasebook” — a glossary of enchantment for the whole Earth. Not just a record of old words, but a living practice.

So this is your invitation. To begin your own phrasebook. One walk at a time.

In doing so, you might find the landscape coming alive in you again.

And in a world that increasingly flattens and speeds past, this is no small act of resistance.

As the saying goes, how do you climb a mountain? One step at a time.

Maybe, then, the answer to how we reclaim the natural world around us is: one word at a time.

Have fun with it. Try it.

I am looking forward to my walk today.