One spring morning near Kinsale Harbour, just a short walk from the fancy yachts and bustling restaurants, I ducked into a line of trees carrying a small pointed knife, a length of plastic tubing, and a container. This wasn’t a woodland, just a small stand of birch trees, probably planted by the council as ornamentals some twenty years ago. Among those trees, I found my specimen. Carefully, I bored a hole into the bark of a young, silver-trunked tree, twisted the tube into place, inserted the other end into the plastic bottle, and set it on the ground. Now, I had to wait. How long, I had no idea.

At the time, I was studying sustainable living and growing curious about wild foraging. That day, I wanted to try collecting birch sap for myself. This clear, slightly sweet liquid has been prized as a refreshing drink and a health tonic for centuries. Rich in minerals and antioxidants—and, more importantly for me, entirely free—it was the perfect foraging experiment. Interestingly, in recent years, even Bord na Móna, the Irish peat company, has tapped into birch sap collection as part of its efforts to diversify. It’s fascinating to see a company historically tied to industrial-scale extraction embrace something as delicate as harvesting sap from birch trees.

But less of that, my efforts were on a much smaller scale. When I returned several days later, I checked the bottle. Sure enough, there was sap gathering inside, though not the liters I’d hoped for. The small amount I managed to collect barely filled the bottom of a jar—a far cry from the bountiful supplies described in foraging books. I took it home feeling both triumphant and slightly underwhelmed. To this day, I can’t recall what I did with that sap—whether I drank it, experimented with fermenting it, or simply stared at it, marveling at the effort it took to collect. What I do remember, though, is that this little adventure marked my first close encounter with the birch tree and its quiet generosity.

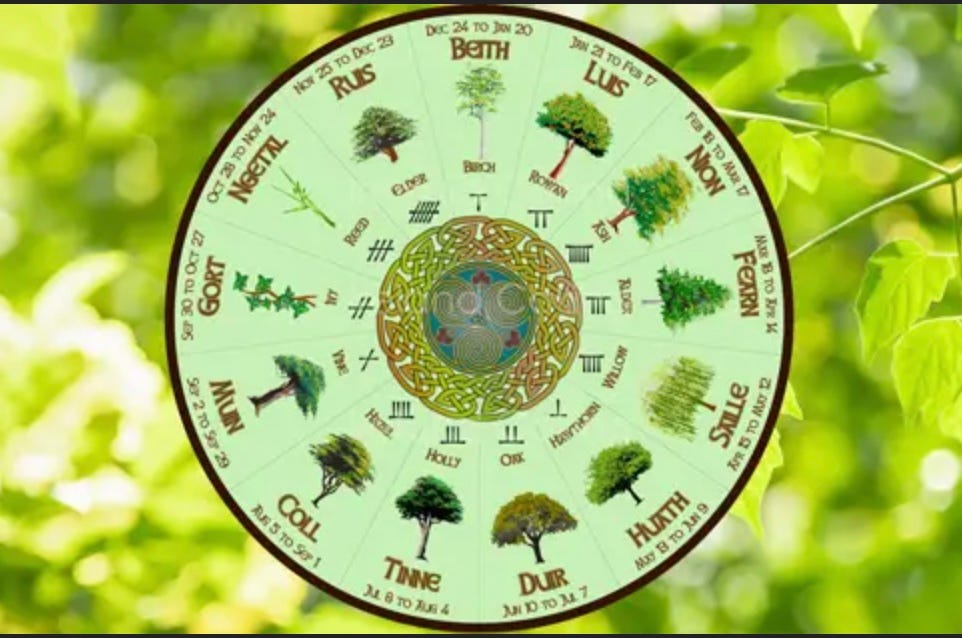

So, to begin this series on the trees of Ireland, I take inspiration from Robert Graves’s Celtic Ogham calendar, in which each month is assigned a tree. Appropriately, we start with:

Birch (Beth): December 24 – January 20

The Pioneer

The birch is known as a pioneer species—one of the first trees to occupy new ground, cultivating the conditions necessary for an emerging forest. I learned this while studying soil science. As any organic gardener understands, we are not ultimately growing plants but soil. With this in mind, what makes the birch so important and unique?

Let’s start with soil. Not all soils are created equal, nor is the life within them the same. Picture a grassland devoid of trees. The bacterial composition in such a landscape does not support tree growth. Trees thrive in soils dominated by fungal life—hence why mushrooms are more abundant in forests than in fields. Grasses, on the other hand, actively compete with and suppress trees, preventing them from taking hold. Plant a young oak tree in a grassy field, and it will struggle to survive. But not the birch.

As a pioneer species with a lineage spanning millions of years—dating back to when the first forests began reclaiming grasslands—the birch thrives in challenging conditions. Walk across a barren patch of land, a wild heath, or a forgotten bog left drained and abandoned, and you’ll likely find birch trees beginning to grow. This is why Bord na Móna is planting birch trees; they can survive and thrive in waterlogged, acidic soils. These resilient trees represent the continuation of an ancient ecological process. As birches mature, shedding leaves and interacting with the soil through their roots, they gradually create the conditions necessary for other trees—like oak and ash—to take root and thrive. This process, called succession, places the birch at the forefront of natural evolution.

Folklore

A tree expert in West Cork once asked me my opinion on the gender of different native trees. It seemed a strange question, but he was tapping into an ancient aspect of trees in our lives: their symbology. The birch required little thought—it is female, specifically a young female, a maiden. In Celtic wedding ceremonies, couples would sometimes jump over a birch branch or broom as a symbol of fertility and union. The birch was seen as a representation of feminine energy and the divine feminine, tied to nurturing and life-giving qualities. Its distinctive white bark shines like a gleam of hope against the bleak greys of winter.

This symbolism aligns with its place in the Celtic Ogham tree calendar as "Beth," marking the return of light and hope after the winter solstice. Fittingly, it symbolizes new beginnings.

Ecology

The birch, for all its resilience and pioneering spirit, is not a tree of great age. Unlike the oak, which can endure for centuries, or the yew, which seems to defy time altogether, the birch lives a fleeting life by comparison, typically reaching around 40 to 60 years. Yet, in its short lifespan, it offers immense ecological value.

I’ve climbed birch trees myself, not for the sap this time, but to harvest birch polypore fungus. This pale, leathery fungus thrives on the birch’s trunk, especially in its later years. Known for its medicinal properties, birch polypore has been used for centuries as an antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory remedy. It’s even said that Ötzi the Iceman, a 5,000-year-old mummy discovered in the Alps, carried birch polypore. Harvesting it is a humbling experience, climbing the smooth, silver bark and feeling the tree’s quiet support beneath your hands—a living reminder of how interwoven nature’s offerings can be with our own well-being.

Beyond their wild habitats, birches have found a cherished place in gardens and urban designs. Their elegant, silvery bark and delicate, fluttering leaves make them a popular ornamental choice, especially in contemporary landscaping. The dappled shade they cast is gentle, never oppressive, allowing other plants to thrive beneath them—a quality that suits its role as the pioneer of new forests.

Years ago, I helped plant a row of mature birch trees in the village of Kilbrittain. They were twenty feet high, uprooted that morning from a local nursery, and transported in a trailer to the site. The planting holes were dug with a digger, and each tree was winched into place. That was over a decade ago, and now, every time I drive through Kilbrittain, I glance at the trees and note that they’re all still there, growing steadily.

As I begin this series on the trees of Ireland, the birch seems like the perfect place to start. Its fleeting life is a testament to the power of beginnings, its ecological role a reminder of nature’s resilience, and its symbolism a beacon of hope and renewal. From the wild to the ornamental, the birch’s presence in Ireland is a quiet yet vital one—just as I found all those years ago on that spring morning near Kinsale Harbour.

Happy new year everyone

Keep an eye out for those birch trees in the wild and maybe run your eyes along the bark, you might get lucky and spot a polypore!

Till next time

My 50% Offer of a Years subscription is still live till Jan 12th.

Sending a welcome and thank you to all my new subscribers.

Always happy to hear from you all

The Birch Tree is a great favourite of mine.I frequently stop to admire them while out on my daily walk.There are a few mature trees in Squirrel Forest in Ryevale,they stand out with their beautiful silvery bark.