And the wheel has turned again, bringing us to our next Trees of Ireland post—and this time to one of my favourites. A tree that lends its name to this Substack and one of the great trees of this land: the oak.

It’s somewhat ironic that, as I sit down to write about a tree that represents strength, endurance, and forbearance, I find myself shaking off the tail end of a head cold, feeling anything but strong. I was at a dear friend’s wedding recently—one of those gatherings of wild joy and reconnection—and word’s gone around that a good few of us caught something in the aftermath. It seems I got off lightly. Others were bed-bound with fever; I was upright, but fading fast by Friday. And so, this week, I’ve been supping hot brews of echinacea, raw Irish honey, and just a touch of poitín—for purely medicinal reasons, of course. It’s a strange thing, a head cold under summer sun. Something about it feels out of place, like winter lingering in the bones.

And yet, the oak waits.

First Encounters

In the absence of our ancient forests—so many of which were felled during the Cromwellian era—we are left seeking our finest specimen trees in unusual places. Many now stand not in wild groves or sacred clearings, but within the grounds of old estates, where they were once planted for ornament or shelter. One such place, close to where I grew up, is Castletown House in Co. Kildare. There, scattered across open fields, are several great oaks—proud and solitary, with room to stretch their limbs wide and breathe deeply into the sky.

Whenever I return from travels abroad, Castletown is often my first stop. There is a particular oak I always visit—one whose presence has become a steady companion in my comings and goings. I lean my back against its broad trunk, close my eyes, and let it help recalibrate me to the slower rhythm of home. It’s a quiet ritual, but one I hold dear.

Another famed oak of Ireland is the Brian Boru Oak, found near Killaloe in Co. Clare. Said to be over a thousand years old, legend holds that it grew during the lifetime of Brian Boru himself—High King of Ireland—who was born nearby and once ruled from this region. I’ve visited it twice. The first time, I found myself drawn into its branches, unsure if I should climb or simply admire. But climb I did. And when I jumped back down, unsure of the rules I’d just broken, I stumbled—straight into an electric fence. There was my answer, perhaps. A reminder to approach such elders with humility.

To experience a true Irish oak woodland—where the oaks still reign and the understorey is rich and alive—you must journey to Killarney. There, in the shadow of the MacGillycuddy Reeks, lie the last remaining fragments of Ireland’s ancient oak forests. I’ve spent long days in those woods, walking without plan or destination, letting the twisting paths of deer and the pull of mossy silence guide me. These are places of magic and memory, where time folds in on itself.

And yet, I go there less often now. The rise of Lyme disease in recent years has given me pause, especially in forests thick with deer and thus ticks. Still, the memory of those moss-draped boughs, the hush of green light through leaf, lives on. When I think of oak, I think of those woods.

A Tree of Kings and Ancestors

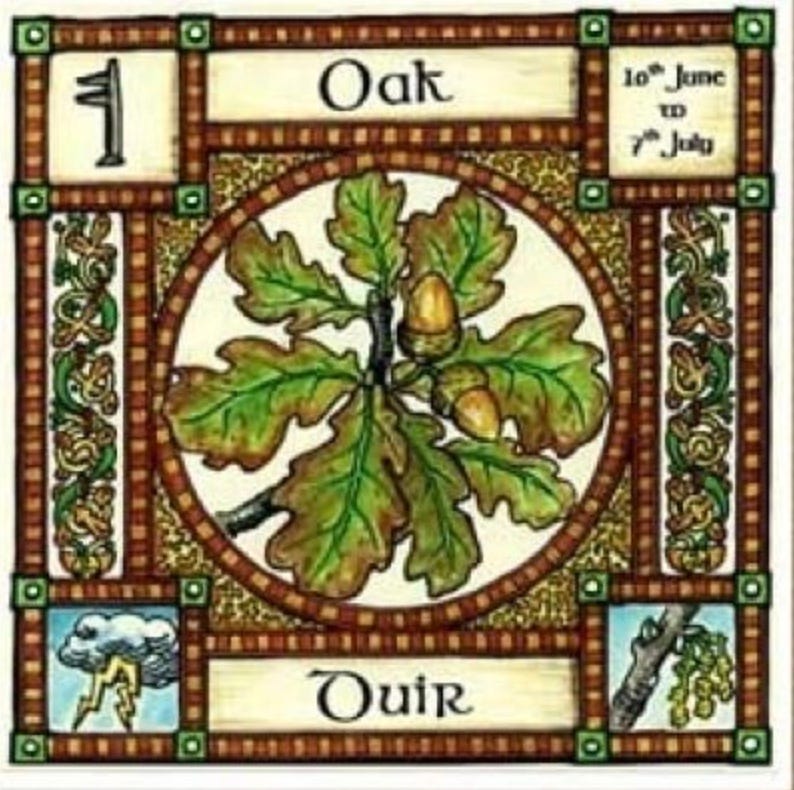

The oak, dair in Irish, is a cornerstone tree of this land—one of the noblest in our native forest, both physically and symbolically. It’s often said that where the oak stands, the people gather. For centuries it has been a marker of sacred ground, of meeting places, and seasonal rites. The druids held their councils beneath oaks; ancient kings were inaugurated under their branches. There is something about the oak’s bearing—its wide reach, its deep roots, its immense presence—that speaks of steadiness and sovereignty.

Even the word dair lives on in our place names. Kildare—Cill Dara, the Church of the Oak. Derry—Doire, meaning oak grove. Derrynaflan, Dromod, Derryconnell. These are places where the oak once stood in abundance, where its roots still echo through the soil.

In Irish lore, the oak is said to be the doorway between worlds. A guardian of wisdom and an elder of the forest. It connects sky and earth, hosting the high nests of birds and sheltering the small lives below. It is no wonder that the word duir, the old root of “door,” shares its etymology with oak. This tree is an opening, an invitation.

Ecology and Interconnection

As an ecological being, the oak is without equal. It supports more life forms than any other native tree in Ireland. Over 280 species of insects rely on it. Its acorns feed birds, mice, badgers, and wild pigs (if you’re lucky enough to live where they still roam). Its branches host lichens and mosses, while owls and squirrels take refuge in its hollows.

Oaks are also community trees. Though they stand tall and proud, beneath the surface they are often connected through networks of mycorrhizal fungi, sharing nutrients and even warning signals with nearby trees. In this way, the oak embodies the paradox of sovereignty and interdependence: it stands alone, yet it never truly is.

Medicine and Myth

Unlike the hawthorn or elder, the oak isn’t often used in traditional herbal medicine for the common ailments of the people. Its medicine is deeper, slower—more for the long game. The bark, high in tannins, has been used as an astringent and for healing wounds. But more often, its power has been invoked symbolically—in rituals of strength, rites of passage, and acts of protection.

The Druids revered it above all trees. They gathered below, performed rituals in its shade, and regarded it as a direct link to the divine. It was believed that lightning was more likely to strike an oak than any other tree—a sign of its sacred charge, its willingness to channel the fire of the gods.

In the old triad of Celtic sacred trees—oak, ash, and thorn—the oak is the anchor. The one who holds the centre.

Ogham and the Inner Path

In the Ogham, oak is represented by the letter Duir, meaning “door.” It signifies stability, wisdom, and endurance. It is the tree of the threshold, the strong gatekeeper who holds firm as we pass from one stage of life to another.

When we encounter oak on our path, we are asked to stand tall in our truth. To hold our ground. To remember who we are and what we carry. This is not a tree of quick fixes or fleeting inspiration, it is the steady walk.

A Final Note

As I write this, I can feel the remnants of that cold lifting. The sun warms the walls of the house. The kettle is on again.

Perhaps that’s the teaching of oak—not to force, but to stand firm in our roots, open our branches to the sky, and trust that what is meant to endure will do so, in time.

Amazing how the place names were used to name, in turn, places in Canada : Kildare, Kilarney, etc.

If the oak is a door, it surely also often is the floor!

I learn something new every week from reading your Substack.

That was very interesting.