This is the first of three parts of a Travel story I wrote during a Writers Retreat in Guatemala several years ago. It is set in the desert of Tabernas in Almeria, southern Spain. I spent quite a lot of time in Almeria between the years 2009-2013, and had more than a few interesting experiences.

Part 1:

They told me to follow the Rambla: “There are a lot of interesting people living out there that you ought to meet.” So I followed it straight into the desert of Tabernas in Almeria, in the far southeast of Spain. I was a young man then, in my late twenties, alive with youthful inquiry, with more questions than answers under my belt. I figured that anyone who chose to live in a place like this might have something interesting to say—maybe even something to teach me.

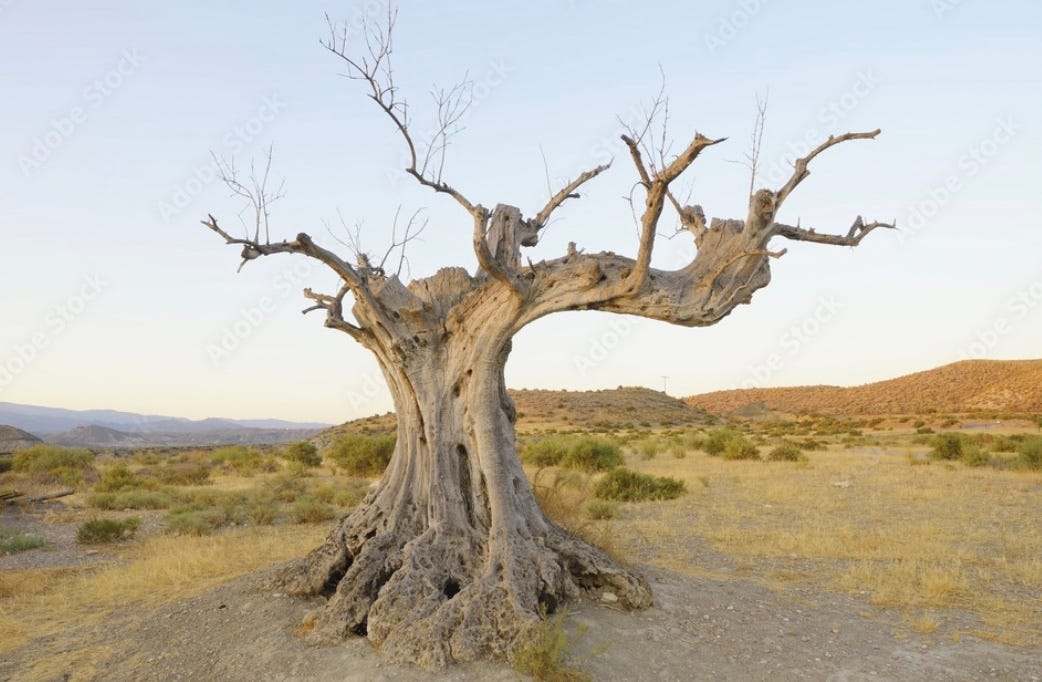

On a morning with no chance of rain, I walked the Rambla, the name given to the dried-out riverbed, a stretch of flat earth and red ground that winds through the scrub and crumbling desert rocks. The Alhamillas mountains rose in the south, and behind them was the Mediterranean Sea and the coastline of Cabo de Gato.

But I was here for the desert—for the land where Sergio Leone shot his Spaghetti Westerns. Where men on the edge of the law forged their own paths, for better or worse, the mythology of those films was soaked into the landscape.

The first sign of human habitation catches my eye—a blue flag tied to a pole at the entrance to someone’s land. Is this Lawrence’s place, I wonder? I was told to meet him first. I enter the enclosure—and that is the right word—passing through a fence made of bamboo canes and metal bars, with a sign painted in fat white letters on old plywood: “Private. No entry.” The yard around me looks like a salvage depot, a playground of found objects dragged in from the desert—abandoned projects, discarded structures, an old fridge lying on its side, and most bizarrely, a sack of broken dolls that looks like it fell out of a child’s worst dream.

Two dogs come charging through the yard towards me, and as quick as their bark, a voice calls them back. Reluctantly, they retreat. It’s a man’s voice, high-pitched and erratic but firm. I can hear him rummaging through things out of sight—the sounds of metal banging off metal, and objects being thrown aside. I wait a moment, then he comes into view. As he approaches, beaming broadly, he thrusts a tremendous hand into mine, causing it to tremble as if a jackhammer had come to life.

“I’m Lawrence,” he says, brushing his hands down his jeans. I tell him why I am here and where I came from, and he listens with interest.

“Okay,” he says, “you’re here now, and your timing is good. I was about to take a break.”

Lawrence invites me into the tented structure that he calls his home and starts to prepare tea. I sit down on the benches by the main table—a heavy lump of wooden planks pinned together and illuminated by a single hanging lightbulb. The kitchen is stocked like a wartime rations store, full of jars and a line of blue plastic drums with words scrawled on their sides. I can see “trigo,” which I know means flour. There are stacks of books and magazines on the shelves, covering much of the perimeter. The word “survival” in thick black letters stands out on one spine. I feel like an object blown in from the desert that has roused this man’s interest.

“Do you know where I’m from?” Lawrence asks. “I’m one-quarter Romanian Gypsy, one-quarter Native American, one-quarter English, and one-quarter Polish.”

He pounds the kitchen counter with his palms and leans back, laughing.

“Yeah, Gypsy, Native American, English, and Polish. My father was a gamekeeper on a big estate in England. I lived with him for a few years, and he used to take me out hunting with him.”

Lawrence sits across from me. His wiry, muscular frame, six feet six inches tall, arches over the space as he sways back and forth, picking splinters of wood from the table. He is like an old dog with one open eye, and I watch his hands slide along the surface—the fingers like tree roots, the skin dark and tanned.

“What was the family of that estate called?” Lawrence asks himself, rubbing his chin. “The Underwoods, that was it. Wonderful people, big family; they had seven children. I used to run around the fields with them as a child.”

Candlelight flickers off the dark recesses at the back of the tent. Nothing is fully revealed. I strain to see something—there’s a faint clicking sound.

Lawrence continues, “Hah, and then I kissed the youngest daughter, and that was that. I wasn’t allowed to play with them anymore.”

He throws his head back and laughs. I laugh a little with him. I’m beginning to settle into his energy and come around to liking him. This rouses the others in the tent.

I return my gaze to the source of the clicking sound and let my eyes settle there, and then I notice them—two more people, a man and a woman, I think, staring into faint computer screens. Neither has spoken yet or turned to note my presence.

“Debs, where’s my gift from the Blackfoot?” calls out Lawrence.

“In the back,” she replies without looking away from the screen.

Lawrence goes to the back of the tent. “It’s wrapped in some green fabric on one of the boxes,” Debs says.

Lawrence returns to the table with a cloth in his hand. “Okay, here we have it.” With ceremonial delicacy, he places the cloth on the table between us and lets it rest there. He reaches out, uncurling the edges, revealing a large knife.

“Something else, eh?” Lawrence says, watching my reaction. Light and shadows flicker across the blade as we stare at it. It looks heavy, like a lump hammer. The blade is cold and about fourteen inches long; the steel is dark grey, turning lighter at the edges. There’s a smell of old leather on the handle, and red and black beads on thick threads hang from it.

“It’s from the Blackfoot tribe,” Lawrence says.

“It’s beautiful,” I reply, wondering where all of this is leading.

“Pick it up,” Lawrence says. “But don’t touch the edge. It’ll cut.”

I had hoped for a cup of tea and a chat about life in the desert, but those hopes are now fading fast. I stand poised between excusing myself and leaving, or simply surrendering to my faith. Yet, in Lawrence, there is also an island of safety and goodwill amidst the dark, brooding energy of the space and the avalanche of words and sensations. So I reach out and grasp the handle of the knife, treating it like a museum piece, laying it across my left palm. Lawrence never takes his eyes off me.

“What’s this?” I ask, pointing out the dark green gemstone on the handle.

“I have no idea,” responds Lawrence, casting my question aside like a scrap of unwanted paper. He leans forward over the table, his eyes intense.

“Were you ever initiated?” he asks. The question catches me unprepared as I note the nearest exit.

“How do you mean?” I ask.

Lawrence considers his response. His voice has quieted down and become slower. “Well, let me put it this way. I would cut myself with that in front of you and instruct you to do the same if you were my son. You know what I’m talking about? That knife you are holding is for rituals.”

I lose the power of speech. Lawrence sees my discomfort and, like a deer reacting to danger, he changes direction.

“Let’s go outside,” he says, standing up and walking towards the door. I am still at the table, gathering myself, when Lawrence’s head pops back inside. “And bring the knife!” he calls out to me.

I’m back outside in the bright light of the Tabernas desert. The washed-out, hazy blue sky has just enough cloud to take the bite off its heat. It is the part of the day when the sun has settled at its highest point, and you brace yourself for some hours of heat.

“Come on, give me a hand,” Lawrence calls to me. He is standing at a wooden table with something lying across it. I walk over with the knife and see a young goat, dead and splayed between us. It is resting on its side, its legs frozen as if it is going to leap from a rock. Blood is pooling under its neck.

“All right, you see that? You’re the assistant.” He waves his hand over the line of bowls, clothes, knives, and plastic bags in front of me. The cup of tea and chat fade further into the distance. I now have a part to play in dismembering a goat. I stand submissively across from Lawrence, at the total whim of his instructions. I don’t want to show weakness or let on that any of this is difficult for me.

The dismemberment begins. Lawrence knows what he’s doing; his hands and the knife flicker about in front of me. Bags and bowls fill with different types of offal and organs. He bends down low, staring inside the carcass, running his fingers along the ribcage, and casting pieces of flesh to one side.

“Keep scraping the table clean; there’s a bucket there,” he instructs, suddenly all businesslike and serious. He hands me a blunt butcher’s knife with a scabbard wrapped in black tape. I use it to clean up the scraps. That is now my job. Lawrence cuts and slices, waves the knife at flies, and cuts again, and I keep the workspace clean. He is teasing away the skin from the different limbs, pulling it loose, then moving to another piece.

"Hand me the saw," he calls out. The muscle in his arm contracts, and the sound of the blade hitting bone fills the air. I wince and close my eyes. When I look again, the goat's head is lying in a metal bowl, staring up into the sky.

Lawrence stands to his full height and rubs his hands down his side.

“Okay, here we go; hand me the ceremonial knife.”

The knife has been waiting at the side of the table. I pick it up, place it in Lawrence’s blood-stained hand, and watch him lift one half of the goat's torso. He holds it open with both the back of his hand and his lower arm and peers inside, his eyes serious and focused. Time seems to slow down as the knife hovers, held delicately in one hand, the tip of the blade pointing towards its destination. It enters, and I dare not move or make a sound. I steady my breath. Lawrence’s focus is taken up entirely by the task; his breath is a whisper.

“We are each going to eat a little.” He says it quietly. “This is a show of respect for the goat's life; we have to mark its passing. A small ritual between two men,” he adds after a pause. “That okay?” he asks.

I nod in agreement, knowing that I am beyond any other response by now. We are two men with blood on our hands, so I await my fate.

When the blade is revealed again, the goat's heart lies across it. Lawrence cuts off a few thin slices and holds one towards me on the blade. I have lost all autonomy and am now following all instructions. But I am saved, in a sense. The dogs explode into life behind us, and I turn to see a stout man entering the compound. He carries another animal's skin in his hand.

“Oh God,” I think. But he walks straight to the table, and his soft tone and smile settle me.

“Phil! Just in time, we’re tasting the heart. Want to try?”

“Not a chance,” Phil responds without a hint of hesitation. I’m stunned. The sureness in his voice is a revelation. It elevates him to some kind of hero. I have none of that composure inside me, and in that moment, I long to access it.

The two men examine the goat skin, assessing its suitability for a drum, when Lawrence says,

“Well, Phil, this young man is visiting the community around here. Care to show him your place?”

“Sure,” responds Phil.

Lawrence casts the knife to the side of the table, and all the seriousness of the moment fades away. But I still have a piece of goat heart in my hand. I’m anxious that Lawrence will notice. He is chewing on his and chatting with Phil when he suddenly swings around to face me and offers his hand.

“This is a good young man, Phil’

My time with Lawrence comes to an end. He thanks me and insists I visit again.

Phil and myself walk back into the desert. The silence feels heavier now, as if the weight of the ritual still lingers in the air. My hand, still warm from the knife’s handle, feels like it belongs to someone else. I glance over at Phil, who is walking ahead, his pace steady, his expression unreadable. He moves with the certainty of someone who has long accepted the ways of this land.

As we step into the shade of a ravine, the harshness of the day begins to soften, and a new kind of understanding stirs within me. The desert, with all its starkness, its cruelty, and its beauty, has carved something into me, though I can’t yet name it. I feel the echo of Lawrence’s presence—his unfiltered, wild spirit—and wonder what it means to truly belong to a place like this.

We don’t speak much on the way back. The landscape itself seems to offer all the answers we need. The silence between us is a kind of peace, a recognition that what just happened is not something that needs to be explained. The experience, the blood, the knife—it’s all still there, lingering in the spaces between us.

And as we walk, I realize this desert will stay with me, not as a memory, but as a piece of myself that I never knew was missing.

Part 2 next week…..