Happy 1-Year Birthday to The House of Oaks and Owls!

On February 12th last year, I published my first post, setting my intentions for this project. I launched it with a mix of excitement and curiosity—would anyone care to read it? But beyond that, I knew that committing to a weekly practice would bring discipline to my writing, something essential for honing any craft.

If nothing else, even if I had no readers at all, I loved the idea of building an archive—a body of work I could one day revisit, refine, or perhaps even shape into a book. A House of Oaks and Owls collection, if you will.

Looking back at the opening paragraph of that first post, the heart of this project remains unchanged:

My hope is that The House of Oaks and Owls will be thought-provoking, educational, and demanding in the best way—appealing to those drawn to contemplation, nature, and spirituality. To those who feel the world is unraveling, that the distance between humans and nature is widening, and who long for something more solid and beautiful. The world aspires to be loved and appreciated, and I think it’s time we attend to that.

One year in, this intention still feels the same. I’ve been attending to these themes and can see how much of my writing touches on my home of Ireland. Yet, on a more universal level, I’ve explored how nature and landscape can serve as both sanctuary and spiritual guide—this theme continues to fascinate me.

I began this Substack while in Guatemala, and it is here that I am writing this now. As many of you know, I have a humble cabin home in the valley of Tzununá, Lake Atitlán—a place I have returned to each winter for four consecutive years. I will head home at the end of March, the time of year when the gardening season begins, when spring is in full flow, and when the first grass cut can usually happen after the long, wet winter. I don’t work as a gardener anymore, but I am still tuned into that cycle and feel drawn to be home when that time arrives.

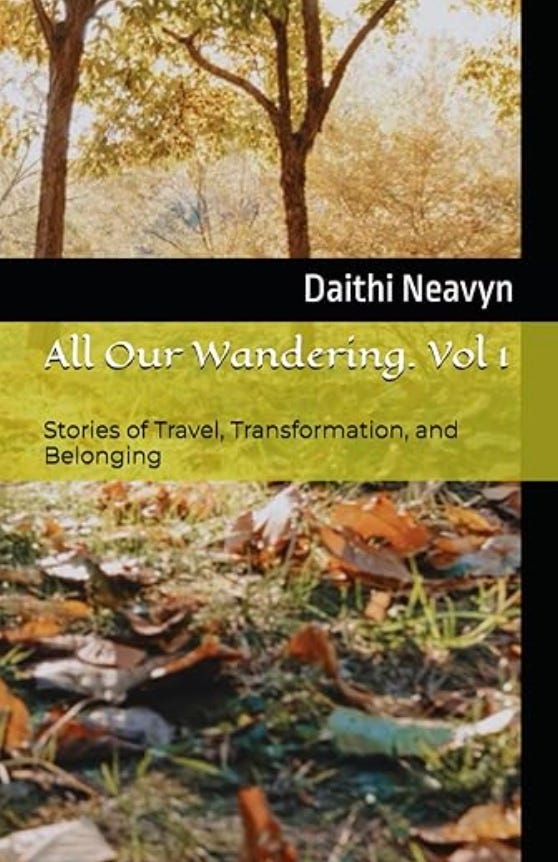

As I reflect on the cycles of return—both in nature and in my own life—it feels like the right time to mention something else I’ve been deeply engaged with: my new book. All Our Wandering, Vol. 1 was released this year, a collection of travel stories exploring themes of movement, belonging, and transformation. I worked on these stories over the course of two writing retreats here in Guatemala, and when I returned last November, I set about finishing it.

It’s a short collection, revisiting tales from more than a decade ago—journeys through the Almería desert in Spain, the landscapes of Thailand, and the vastness of India. Stories that capture fleeting moments of discovery and change.

Now, I’ve begun writing the second volume, which will be predominantly—if not entirely—about Ireland. After years of looking outward, this next collection feels like a return, a deepening of my connection to home. Just as my travels shaped my understanding of the world, Ireland continues to shape my understanding of myself.

If All Our Wandering, Vol. 1 resonates with you, I’d love for you to pick up a copy and take the journey with me. I’m incredibly proud of this collection—it’s a book shaped by years of travel, reflection, and storytelling, and it means a lot to finally share it with the world.

You can buy it here!

Amazon.com. My Book

Amazon UK. My Book

If you do read it, leaving a review on Amazon would be a huge help in getting it out there to more readers. Your support, whether through a review, a recommendation, or simply sharing your thoughts, makes all the difference.

And now, since this is the third Sunday of the month, when I like to share a travel encounter, I’ll leave you with a story that has always stayed with me. It’s about a winter’s day on the fringes of the Burren, an attempt to do things the ‘right’ way, and a lesson in just how deeply land ownership runs in the Irish soul.

One winter, on the fringes of the Burren in County Clare, I set out to harvest hazel. Hazel, being a scrub plant, is generally disliked by landowners in the area, and while I usually forage on wild yet privately owned land, I’ve never been able to fully relax into the task—always half-aware that I was somewhere without full permission.

So, for once, I decided to do things properly. I stopped a passing car and asked who owned the land I had in mind. The driver told me, “That’d be such-and-such’s place—he lives just up the road.” Off I went.

I arrived at a small, simple house, where a very old couple stood chatting in their garden. They looked at me with curiosity as I approached, and I explained why I was calling. To my delight, the old man turned out to be a local legend—a keeper of stories, lore, and history. Over the garden wall, he began recounting tales of the surrounding landmarks, each more fascinating than the last. It was a life-affirming encounter, one of those rare moments when Ireland’s ancient soul and living tradition come together effortlessly in conversation.

Before I left, he gave me his blessing to harvest hazel on his land, complete with specific instructions on how to open the gate. Off I went, feeling exceptionally good about myself and my countrymen—proud, even, that I had taken the respectful route, done things properly, and been met with warmth and generosity.

Less than an hour into my harvesting, I heard the farm gate swing open. Then—an engine revving.

I stepped out of the hazel thicket into a clearing. At first, I saw nothing. Then, from the bend at the top of the field, a car came hurtling down towards me, gaining speed across the rough ground. Before I could react, it swerved sharply and skidded to a stop, blocking the exit.

Out jumped a man, face twisted in rage, and before I could even say a word, he was roaring into my face:

“WHAT ARE YOU DOING HERE?!!”

It was the old man’s son.

I’ve not often witnessed such a pure mix of fear and fury. His voice shook with it. His eyes bore into me. And then came the classic Irish interrogation, thick with suspicion:

“Who are you with?”

Now, to those unfamiliar, this phrase, in a certain Irish context, does not mean, Are you here with friends? No—it means, ‘Who are you and who are your people?’

I tried to explain. I told him I had spoken with his father, that I had permission, that I even had instructions on how to open the gate. But none of it mattered. His anger was all-consuming. I had touched upon something deep, something raw—a wound buried in the Irish psyche: trespassing.

It was primal, centuries in the making. The land, hard-fought and hard-kept, was sacred, and I was an intruder.

No reasoning, no explanation could undo that.

The reason he sped up the field first was to check on his cows. I expect he counted them, and, assured they were all still there, he came looking for the owner of the white van with the Cork registration parked inside his field.

I was evicted—on the spot. Everything I had harvested was to be left behind. I was marched back to the gate, the weight of generations pressing down on the moment.

And so, I departed, empty-handed but with a lesson well learned: in Ireland, land may be scrub, and hazel may be unwanted—but the ghosts of the past are never far from the present.

Also, let’s be honest—sometimes, a man is just a bit demented.

I look forward to reading your weekly Substack.The encounter with that raging man must have been scary.It was just as well that he didn’t call the Guards otherwise you could still be in the field 😀.